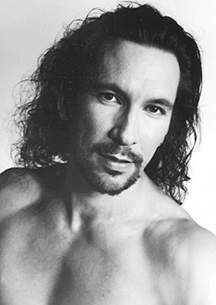

Marshall Pynkoski Opera Atelier by Wah Keung Chan

/ October 1, 1998

Version française...

Toronto’s baroque opera

company Opera Atelier is busy gearing up for its millennial production of Jean-Baptiste

Lully's opera Persée, which will open in Toronto and tour the world in the year 2000.

They finished the first phase of their training in August, running a dozen singers through

their paces. More than ever, Opera Atelier founder Marshall Pynkoski is immersed in the

recherché world of baroque performance practice, trying to reproduce the gesture and

movement of singers and actors as they were seen at the court of Louis XIV. Toronto’s baroque opera

company Opera Atelier is busy gearing up for its millennial production of Jean-Baptiste

Lully's opera Persée, which will open in Toronto and tour the world in the year 2000.

They finished the first phase of their training in August, running a dozen singers through

their paces. More than ever, Opera Atelier founder Marshall Pynkoski is immersed in the

recherché world of baroque performance practice, trying to reproduce the gesture and

movement of singers and actors as they were seen at the court of Louis XIV.Opera Atelier was founded in 1985 by artistic directors Marshall Pynkoski and

Jeannette Zingg. Pynkoski and Zingg originally danced with the Canadian Opera Company

ballet when Lotfi Mansouri was general director. "Mansouri always tried to get the

ballet involved," said Pynkoski. "That was my first experience with singers,

seeing the differences between singers' rehearsals and dancers' rehearsals. Back in the

early 1980s Jeannette and I started attending performances given by Tafelmusik. I was

intrigued with the tunes and the pitch and the enormous physicality involved in playing

authentic instruments. I became captivated with the music.”

"When Tafelmusik started moving into vocal repertoire, I found

it the most ravishing music I had ever heard, though it was often from obscure operas that

were never performed. People thought these operas were hopelessly outdated, but these same

people admitted they had never seen or heard or been involved in an opera by Charpentier

or Lully." Pynkoski decided to prove the doubters wrong by starting Canada’s

first opera company specializing in historically informed performances.

A staged Opera Atelier production involves elaborate period

costumes, baroque dancers, opera singers and Pynkoski's staging. In an address to the

National Association of Teachers of Singing in Toronto last July, Pynkoski explained his

ideas on baroque gestures.

According to Pynkoski, "The 18th century was the great age of

storytelling. Operas were word-dense and singers described their hysteria rather than

demonstrating it. People felt real emotion represents real life, and they went to the

theatre to see art, not life. If the audience saw tears on stage, they would be fascinated

rather than become drawn into the drama."

"The 18th century realized that there had to be a technique to

help singers to move that would look natural and allow them to sing comfortably and

naturally. They observed that in real life, people move when they talk, with gestures.

Gestures are from the elbows. The elbows control the arms. Movement is circular from the

hairline, and are quick, easy and articulate. The arms go only so high and so low. If the

hands are too high and extended, it is difficult for the audience to concentrate on both

the face and hands at the same time. A singer's movement must reflect the text. Individual

gestures happen on individual words and are suspended to the next important word.”

When it comes to a da capo aria, Pynkoski says that the repeat

section should be in front of the stage, "There is no reason for a da capo movement.

It's about the music. I only allow three gestures: play to the left, play to the right,

and play to the balcony."

Opera goers will get a chance to see the fruit of Pynkoski's ideas

in Opera Atelier's staging of Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro. "The opera is not just

a visual story; there is so much humour within the text. Jeremy Sams' translation for The

English National Opera caught the flavour and the raunchiness of the period. When I read

the translation, I knew I had to produce it."

Opera Atelier performs Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro in English at

Toronto's Royal Alexandra Theatre Oct. 22, 24, 27, 29, 30. Ticketing: 416-872-1212 or

1-800-461-3333.

Version française... |