|

|

|

Visit every week to read Norman Lebrecht's latest column. [Index] Visit every week to read Norman Lebrecht's latest column. [Index]

Mahler's Going for a song By Norman Lebrecht / May 13, 2004 | |  |

One summer's day at the turn of the last century, a composer, feeling lonely, wrote a song which he called 'I'm Lost to the World'. It was not an overnight hit. In fact, the composer was disregarded for so long that he was practically out of copyright before his music took off, in the 1960s. One summer's day at the turn of the last century, a composer, feeling lonely, wrote a song which he called 'I'm Lost to the World'. It was not an overnight hit. In fact, the composer was disregarded for so long that he was practically out of copyright before his music took off, in the 1960s.

He wrote out the song in two versions, one with piano accompaniment, the other for full orchestra. The second manuscript he presented to an eminent musicologist, inscribing it 'to my dear friend ... who could never be lost to me.' It remained in the scholar's home until his death in 1941, when it vanished into Nazi hands. That document, 12 pages long, will be sold at Sotheby's next Friday (21/5) for around half a million pounds. He wrote out the song in two versions, one with piano accompaniment, the other for full orchestra. The second manuscript he presented to an eminent musicologist, inscribing it 'to my dear friend ... who could never be lost to me.' It remained in the scholar's home until his death in 1941, when it vanished into Nazi hands. That document, 12 pages long, will be sold at Sotheby's next Friday (21/5) for around half a million pounds.

Since price is the prime measure of cultural value, what we are witnessing is the sale of the most important song of the 20th century. Since price is also the engine of avarice, there is an unpleasant history attached.

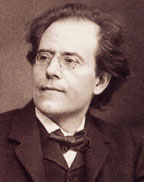

Gustav Mahler composed 'Ich bin der Welt Abhanden Gekommen' in August 1901 at a crossroads in his stressful career. At 41 he was director of the Vienna Opera, the most talked about conductor in Europe. As a composer, he was a flop. His first two symphonies had been drowned in critical derision, two more were stuck in a drawer and he had just written a fifth. Some months earlier he almost died of a rectal haemorrhage. On leaving hospital, he learned that the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra had replaced him as chief conductor with a paltry balletmaster. Mahler's modernisations at the Opera made him many enemies. He saw scant reward for incessant effort.

A poem by Friedrich Ruckert expressed his existential isolation and he set it swiftly to music. Returning from his summer break, he gave the piano sketch of the new song, as if worthless, to a travelling companion.

But Mahler's loneliness was about to be broken. Back in Vienna he met a captivating blonde half his age at a post-concert dinner and, within weeks, was married. Alma, a celebrity predator - she subsequently married the Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and the bestselling novelist Fritz Werfel - would betray Mahler body and soul. But she brought with her a gust of intellectual stimulus and a circle of modern thinkers - Klimt, Schoenberg, Freud - replacing all his fusty old friends, with one stubborn exception.

Guido Adler, who grew up in the same small town as Mahler, clung to him like a college scarf. Adler founded an institute of musicology at the University of Vienna and redefined the discipline. Alma loathed him but respected his influence on musical opinion. On Adler's 50th birthday, 1 November 1905, Mahler gave him the orchestrated manuscript of his solitude song, weeks before its premiere.

Adler's adherence was unshakable. After Mahler's death in 1911 he published a monograph, campaigned for a public monument and generally promoted his music against public indifference and political hostility. When Austria embraced Nazism in 1938, Mahler was banned as a Jew and Adler's life was in jeopardy. His son secured a family exit permit to the US, but the scholar, now 83, refused to be parted from his precious library. He stayed behind with a daughter, Melanie, imagining that his treasures would earn them immunity. Melanie wrote to Winifred Wagner, ruler of Bayreuth and Hitler's confidante, begging on her father's behalf 'for a letter of protection that would finally secure some peace for me, my possessions and my work' There is no record of any Wagner reply. The library was placed under the protection of a Nazi-approved lawyer, RichardHeiserer, who blocked Melanie's plan to sell the collection intact to a public archive in Munich.

Adler died of natural causes in February 1941 and Melanie was deported soon after to Minsk for extermination. Heiserer became the administrator of their estate which was promptly pillaged by Adler's foremost University colleagues, Erich Schenk, Leopold Novak, Robert Haas. The Mahler manuscript was deemed lost - until it turned up for sale four years ago at a Sotheby's auction in Vienna. The vendor was Richard Heiserer, lawyer son of the Adler's administrator.

Adler's grandson Tom, a California civil rights lawyer, flew in to claim rightful ownership. Heiserer maintained that the song had been freely given to his father by the unfortunate Melanie. The Austrian government, which had done nothing to investigate or prosecute the looting of Adler's library, stepped in to impose an export ban on what it claimed to be a valuable part of the national heritage. The conflict is drily described by Tom Adler in a memoir, Lost to the World, published by Xlibris and available on line.

Tom Adler finally reached a private settlement with Heiserer, the details of which have not been disclosed. As a result, and perhaps as part of the settlement price, the manuscript has now been put on sale in London as Tom Adler's property, without Austrian constraint. Sotheby's, never the loser in such wrangles, have set an estimate of £400-600,000, and there is every likelihood that price will be reached, even breached. Several international institutions will want this manuscript as a cornerstone of their collection, not least the Sacher Foundation in Basle, pre-eminent in 20th century music, and the Austrian National Library which has several Mahler scores. There are also a number of wealthy individual Mahler collectors.

Still, the price of this song is clearly more than just the sum of its orchestralparts. Even allowing for the present-day ubiquity of Mahler's music, no musician would value one Mahler Lied at four times Ravel's Pavane pour une enfante défunte, an early masterpiece of French impressionism which comes up in the same sale.

I have known an entire Mahler symphony go for less than half the price demanded for this single song. What is being purveyed here, therefore, is something rather more ethereal.

It is, I suspect, one of those rare freeze-frames in creation when a great artist stands at the cusp of momentous change, isolated by dint of genius from the rest of the human species. The solitude of Van Gogh's Sunflowers, the daring of Beethoven's Eroica, are moments of this kind. It is not so much the score or the canvas that is precious as the moment of conception, the awesome darkness before the dawning of light.

Visit every week to read Norman Lebrecht's latest column. [Index]

|

|

|