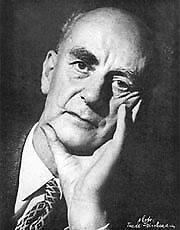

Great Performers - Wilhelm Furtwängler by Philip Anson and Wah Keung Chan

/ February 1, 1998

A glance at

the library bookshelves reveals a dozen books written about German

Maestro Wilhelm Furtwängler over the last decade to coincide with

the 100th anniversary of his birth and the fortieth anniversary of

his death. The current obsession with the role of art and culture in

the Third Reich has also focussed attention on Furtwängler, who was

Hitler's favourite conductor. Last summer I had the good fortune to

interview Wilhelm Furtwängler's step-daughter Kathrin during her

visit to Montreal. Kathrin was a little girl when her mother

Elizabeth married the great Maestro. She was glad to talk about the

growing public fascination with Furtwängler and to share her

memories of their family life in Germany and Switzerland during the

last decade of Furtwängler's life. A glance at

the library bookshelves reveals a dozen books written about German

Maestro Wilhelm Furtwängler over the last decade to coincide with

the 100th anniversary of his birth and the fortieth anniversary of

his death. The current obsession with the role of art and culture in

the Third Reich has also focussed attention on Furtwängler, who was

Hitler's favourite conductor. Last summer I had the good fortune to

interview Wilhelm Furtwängler's step-daughter Kathrin during her

visit to Montreal. Kathrin was a little girl when her mother

Elizabeth married the great Maestro. She was glad to talk about the

growing public fascination with Furtwängler and to share her

memories of their family life in Germany and Switzerland during the

last decade of Furtwängler's life.

Wilhelm Furtwängler was born on January 25,

1886, in Berlin, the oldest of four children and the only one to

become a musician. His father Adolf was a well-known classical

archaeologist and his mother Adelheid was a painter. The boy's

musical talents were evident early: he started piano lessons at age

4 and penned his first composition at age 7.

Furtwängler's earliest ambition was to become a

composer. He started conducting just to earn a living. He never

played in an orchestra, but learned the ropes as a rehearsal

pianist. His father helped arrange a concert for him in 1907 -

Bruckner's Ninth Symphony with Munich's

Kaim Orchestra - which was his first big success. A 1912 concert

conducted by the great Artur Nikisch in Hamburg stimulated

Furtwängler's ambition to become the best conductor of his

generation. He soon became known and attracted a loyal

following.

An engagement with the Mannheim orchestra

led to his appointment as director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Through the 1920s and 30s Furtwängler was considered the foremost

conductor of his time and it is interesting to learn that even his

children were in awe of him. "Looking back I can say he is the

greatest person I've ever met. We all knew that, even as children,"

recalls his step-daughter.

Wilhelm was a good father, loved to laugh

and tell jokes to his children. "The thing I remember best is that

when he played with us he played to win. Some grown ups, when they

play with children let them win, but my father's way was much more

fun." Another anecdote reveals Furtwängler's legendary

competitiveness. One morning her father described a terrible

nightmare he had: "I dreamed I was in a race and I came in

second."

Furtwängler's work ethic was strong. "Goethe

said that genius is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration, which

certainly applies to my father. He had great powers of

concentration. He could sit and memorize a score without being

bothered by all the children making noise around him." She recalls

how he went for a walk every day, following the same circuit for

hours. "He didn't look at nature. He was probably still thinking

about work."

Kathrin also recalls spending her school

vacation in Salzburg where her step-father was  conducting Verdi's

Otello. "They rehearsed a lot more than they do today. We

stood the whole day in the rehearsals and I cried every time Otello

entered Desdemona's room to kill her." She also recalls that at

first he didn't want to do Otello but after it was over he decided it

was a good opera. "He could always find something valuable in the

music." conducting Verdi's

Otello. "They rehearsed a lot more than they do today. We

stood the whole day in the rehearsals and I cried every time Otello

entered Desdemona's room to kill her." She also recalls that at

first he didn't want to do Otello but after it was over he decided it

was a good opera. "He could always find something valuable in the

music."

Furtwängler's fame reached its height during

the Nazi years. His work brought him into close personal contact

with high Nazi party officials, including Goebbels, Göring and

Hitler. The notorious film footage of Furtwängler shaking Hitler's

hand after a concert has done his reputation great harm. Kathrin

tells the story of that event: "That Nuremberg concert was supposed

to be on Hitler's birthday, so my father scheduled it the day

before, thinking Hitler would not attend. He was so furious when

Hitler came to the concert that he pulled a radiator off the wall.

Furtwängler came on the stage and told his musicians to begin right

away. But after the concert, Hitler gave him his hand and he had to

shake it. If you don't know the story, then it is easy to get the

wrong idea from the photo."

Furtwängler was never a Nazi party member,

but he enjoyed official favour, honours, and earned more money than

any other German musician of his day. Endless books and articles

have been written about Furtwängler's involvement in the musical

life of the Third Reich. Katrin describes Wilhelm as a political

innocent who thought he could do good by staying in Germany. "He

stayed in Germany to give the people the gift of his music. He was

very German, his roots were there and he would have suffered in

exile. What was important for him was German culture. No other

conductor knew more about German literature and painting. It was not

just the music, he wanted the whole culture around him."

Whether Furtwängler was a Nazi is still hotly

debated. Michael Kater in his book The Twisted Muse: Musicians

and Their Music in the Third Reich (Oxford University Press, 1997 p.201) claims that he was, while

(as other writers before him) offering examples of people who were

helped by Furtwängler. In any case, Furtwängler was used by the

Nazis and used them in return. He was denazified in 1947, and the

transcripts have become the basis for Ronald Harwood's play "Taking

Sides," which makes its Canadian debut at Montreal's Centaur Theatre

in February 1998.

Furtwängler's final years were unhappy. In

1952, a course of the antibiotic streptomycin damaged the nerves in

his ears, leaving him deaf. Attempts to compensate for his hearing

loss with onstage loudspeakers were ineffective. In 1954 he

conducted his last concert and died after another bout of pneumonia.

Considering how her father dreaded growing old (he always avoided

the local old folks' home) Kathrin considers his death an act of

mercy. "He certainly didn't want to become a useless old man."

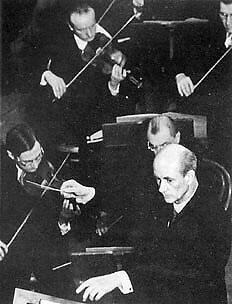

Furtwängler's conducting style can be

studied on several commercially available videos (including Teldec's

"The Art of Conducting" series and the Bel Canto Society's "Great

Conductors of the Third Reich"). He leads his orchestras with a

magisterial intensity, with expressive hand movements but a

strangely stiff back. His daughter explains that this was not a case

of nervousness, "My father was the most relaxed person I've ever

seen. People always remarked on the elegance of his conducting,

especially his graceful turning, but this was partly the result of a

skiing accident. He hurt his neck, so he couldn't turn his head

alone. "

Furtwängler made relatively few recordings in

his lifetime, mostly for EMI, but a wealth of excellent pirate

recordings exist from live broadcasts of the 1930s and the post war

era (a comprehensive discography is available on the internet at the

Website http://www.fornax.hu/wfsh/disco.html ). He

left behind several compositions which he asked his wife not to

promote, hoping they would be appreciated on their own merits. He

wrote several essays on music and conducting. In a letter to La

Scena Musicale Furtwängler's widow

Elisabeth (the English translation of her biography of her husband

was published last year by the Furtwängler Society) declares herself

pleased by the growing interest in her late husband's music and

writings "not only among younger people who know him only from

records, but also among the younger generation of conductors who are

emulating his example in their own work, especially Sir Simon

Rattle, Esa Pekka-Salonen and Christian Thielemann. It might not be

too much to say that Furtwängler is becoming better understood now

than in his own lifetime. There is a splendid irony in that."

Taking Sides opens

at the Centaur Theatre in Montreal on February 24. Info:

(514)288-3161.

In a future issue,

we will look at the music of Furtwängler.

|