Austin Explores "Hungarian Connection"

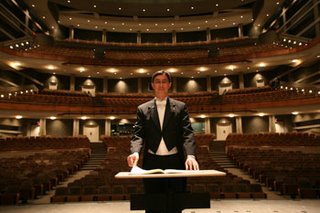

It was a clever idea for Austin Symphony music director Peter Bay to preface a rare performance of Miklós Rózsa’s Violin Concerto with some of Brahms Hungarian Dances. Rózsa was born in Budapest and makes use of Hungarian folk music in his concerto. The major work on the program was Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, a work that has no apparent Hungarian connection. But who can be sure? Besides twenty-one Hungarian Dances and eleven Zigeunerlieder (Gypsy Songs), not to mention the "Rondo alla Zingarese" from his G minor Quartet, Brahms had Hungarian music in his blood.

How Hungarian are Brahms’ “Hungarian” Dances?

Peter Bay chose to program just three of the Hungarian Dances and only the ones that Brahms orchestrated himself from pieces originally composed for piano duet. To my mind these pieces best reveal their charm when they are played by two people – preferably very good friends – seated at one keyboard. But it is understandable that Brahms wanted to capitalize on the popularity of these pieces by making them available for performance by symphony orchestras. Incidentally, the discussion still rages as to whether the music Brahms used as the basis for his dances were really gypsy rather than Hungarian. The consensus is that the music Bartók and Kodály later uncovered in their travels through rural Hungary was both much more authentic and more complex.

Hungarian-Born Miklós Rózsa Prolific Composer of Movie Music

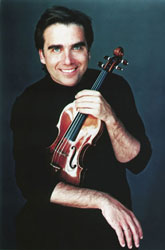

Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995) may have been born in Hungary but he lived most of his life in Los Angeles writing music for the movies. He was very good at it too and his skills contributed greatly to the success of films such as Ben Hur, Spellbound, Double Indemnity, Quo Vadis, and even the Steve Martin comedy Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid. But Rózsa wrote important concert music too. When Leonard Bernstein made his legendary debut with the New York Philharmonic in 1943 there was a Rózsa work on the program: Theme,Variations and Finale Op. 13. And it was Jascha Heifetz who encouraged Rózsa to write his Violin Concerto and gave the first performance in 1956 with the Dallas Symphony. At the time Rózsa was at the height of his career as a film composer. Not surprisingly, the Violin Concerto does sound a lot like film music of the period. It has soaring romantic melodies and lush orchestration. What’s more, Rózsa borrowed chunks from the Violin Concerto for the film score he composed in 1970 for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Not that there is anything wrong with that. The Violin Concerto is a well-made and very attractive piece that deserves a place in the repertoire. And Robert McDuffie is just the man to play it. He recorded it in 1999 for Telarc and lately he has been playing it all over the world, including on a tour with the Jerusalem Symphony.

At the time Rózsa was at the height of his career as a film composer. Not surprisingly, the Violin Concerto does sound a lot like film music of the period. It has soaring romantic melodies and lush orchestration. What’s more, Rózsa borrowed chunks from the Violin Concerto for the film score he composed in 1970 for The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Not that there is anything wrong with that. The Violin Concerto is a well-made and very attractive piece that deserves a place in the repertoire. And Robert McDuffie is just the man to play it. He recorded it in 1999 for Telarc and lately he has been playing it all over the world, including on a tour with the Jerusalem Symphony.

McDuffie Dazzles with Tone & Technique in Rózsa’s Violin Concerto

There are certainly Hungarian elements in the Violin Concerto but they are not the gypsy elements popularized by Brahms. Rózsa makes use of the pentatonic scale and some rhythmic devices characteristic of some Hungarian folk music. But it would be misleading to say that the concerto is “based” on Hungarian folk music. It has a character all its own. When the music is not lyrical it is often virtuosic in the extreme, especially in the thrilling codas closing the first and third movements. I had never heard McDuffie live before and I was immensely impressed by his superlative playing and commanding presence. I was also amazed by the volume of sound he produced. After just a few concerts in the still-new Long Center it is impossible to say what the hall is contributing to the music. But it seems that the hall is very flattering to the sound of a solo violin. In any case, let’s hope that McDuffie returns soon. He is a wonderful artist. And let’s not forget conductor Peter Bay’s contribution to the success of this performance. He and the ASO were with McDuffie every step of the way.

A Scholarly Reading of Brahms’ Symphony No. 4

The concert concluded with Brahms’ Symphony No. 4 in a performance that sounded well-prepared and very satisfying on its own terms. Peter Bay gave us a scholarly view of the score, paying careful attention to balances – the low-lying flute solo in the fourth movement came through beautifully - and maintaining forward motion. Over the years orchestras have grown larger and conductors have tended to make Brahms symphonies richer and more powerful than they were in the composer’s lifetime. We know that at the first performances a much smaller string section was used. On the other hand, orchestras play in larger halls today and perhaps they need to produce a bigger sound for the music to make the same effect.

Orchestral Seating Plans & the Search for an Ideal Sound

Bearing all of these issues in mind I personally would still like to hear a more robust sound in the Brahms symphonies. Perhaps the acoustics of the hall were not entirely sympathetic to the conductor’s approach. Peter Bay and the ASO might want to experiment with different seatings. For this concert the double basses were lined up on the extreme right of the stage and from where I sat they hardly projected at all. Perhaps they could be moved to the left side facing out for better effect. The timpani was placed at the right rear of the orchestra and the sound was distant and muffled. Similarly, the trumpets seemed to disappear in the climaxes. In such matters Leopold Stokowski provides a useful role model. He never stopped searching for better seating plans for his orchestras. He realized that every hall is different, and that there is nothing scientific about the traditional orchestral seating. The point is to try to find the ideal sound for every piece in every place. We can’t do much to physically change concert halls after they have been built but we can certainly try to make them sound better. And Stokowski was legendary for making orchestras sound wonderful.

Bearing all of these issues in mind I personally would still like to hear a more robust sound in the Brahms symphonies. Perhaps the acoustics of the hall were not entirely sympathetic to the conductor’s approach. Peter Bay and the ASO might want to experiment with different seatings. For this concert the double basses were lined up on the extreme right of the stage and from where I sat they hardly projected at all. Perhaps they could be moved to the left side facing out for better effect. The timpani was placed at the right rear of the orchestra and the sound was distant and muffled. Similarly, the trumpets seemed to disappear in the climaxes. In such matters Leopold Stokowski provides a useful role model. He never stopped searching for better seating plans for his orchestras. He realized that every hall is different, and that there is nothing scientific about the traditional orchestral seating. The point is to try to find the ideal sound for every piece in every place. We can’t do much to physically change concert halls after they have been built but we can certainly try to make them sound better. And Stokowski was legendary for making orchestras sound wonderful.

Paul E. Robinson is the author of Herbert von Karajan: the Maestro as Superstar and Sir Georg Solti: his Life and Music, both available at http://www.amazon.com/. For more about Paul E. Robinson please visit his website.

Labels: Austin Symphony Orchestra, classical music, conductors, Peter Bay, Robert McDuffie, Rome Chamber Festival, violin