Vancouver International Jazz Festival 2009: Set 1: Introduction and Trio M

The TD Canada Trust Vancouver International Jazz Festival has a special quality that differentiates it from the vast majority of music festivals. It presents not only an array of headliners to fill the the large concert halls, but it also emphasizes the musicians who represent the bulk of the Canadian jazz scene aesthetics and economy. Approximately 1800 musicians play the festival, and 52% of these are from the Vancouver area while another 15% are from the rest of Canada. I'll stand corrected if any other large North American festival, the Montreal festival for example, can even come close to this track record. The TD Canada Trust Vancouver International Jazz Festival goes one step further to make it the shining star of North American festivals: the restless rolling stone of jazz imagination finds its contemporary expression every June in Vancouver. The TD Canada Trust Vancouver International Jazz Festival spotlights creative Canadian and international musicians in the context of their long-standing collaborations, not in cubby-hole clubs, but in venues with great acoustics and comfortable seating.

One of these collaborative events, Ice hockey: Canada vs. Sweden featuring François Houle and Mats Gustafsson +12 was an extravaganza featuring musicians decked out in hockey jerseys. Two video screens showed vintage hockey matches; the screens switched to scoreboards when one side trumped the other with a goal. Fred Lonberg-Holm from Chicago a had immense fun refereeing the jocular relations between the Canadians and Swedes in a show which featured plenty of roughing and fast-paced improvisational skating. At the end of the match the score was even, Houle and Gustafsson faced off, not with the clarinet v. baritone saxophone, but over a child's board game. Gustafsson easily scored with a slap shot and the players then went through the post-game ritual of shaking hands with each other.

A different take on international collaboration came from the Félix Stüssi 5 + Ray Anderson. Stüssi is a Montréal-based pianist-composer who originally came to Canada from Switzerland. Anderson's original base was Chicago but now it is New York State. Then there was Joëlle Léandre, the French bassist who was ubiquitous at this year's festival, collaborating with a number of people, including a solo-duo set with Swiss improviser Urs Leimgruber. Gigs such as these may not be the economic engines that keep a festival boat afloat in these years of funding cuts to the arts, but over the course of the previous twenty-three annual festivals, Vancouver audiences have been privileged to cutting edge music. For example, in 1992, Bill Frisell told me that festival Artistic Director Ken Pickering was the first person in North America to ask him to play his own music at a festival.

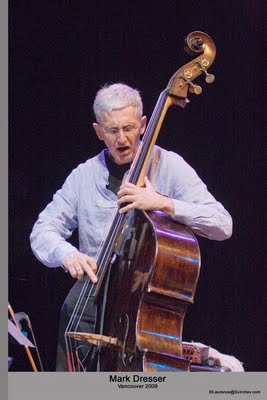

Jazz journalists too-frequently review a festival's music in the chronological order in which they heard the gigs. While this may give a sense of how a festival flows, it is all too easy for the writer to concentrate on making comparisons between and among gigs, writing more about how the writer feels he becomes aurally saturated over 10 days. The range of music at the TD Canada Trust Vancouver International Jazz Festival is too broad, in my opinion, for such an approach. It is not fair to artists to compare a headline set of music veterans with the opening act, typically younger artists who represent the future of the music. In an attempt to keep the ears fresh, I listened to maximum two or three concert sets a day. With this dynamic in mind, I'll concentrate on some of the individual concerts I heard, starting with Trio M (Myra Melford, Mark Dresser, and Matt Wilson).

Trio M

Trio M's concert opened misterioso, seemingly as an open improvisation in slow time. Dresser played long-tones arco in the cello range; Wilson emphasized the toms with flutter anti-theses on the high-hat; Melford played sparingly, almost randomly, as she moved gradually out of the treble range into the mid-range. Then at four minutes, the preamble paid off in a grand anthem-like theme that evoked the strange paradoxical tension between music that is somber and celebratory at the same time. The musicians chose not to sustain this zone of tension for long. With Matt Wilson's explosive "Go!", the song took off as an express-train duo between the pianist and the drummer. From there the song went through multiple variations on themes, time changes, and emotional feel before ending at the thirty-two minute mark.

Many, including myself, had not heard Matt Wilson before. He made a strong impression upon the sophisticated group of listeners who frequented the Roundhouse Performance Center, so I would like to comment on his approach to music making. Wilson's delivery, although he is a thorough modernist, was oddly reminiscent of Joe Morello's, the underestimated drummer who made his mark with the classic Dave Brubeck Quartet. Morello was a drummer's drummer; it seemed that wasn't anything Morello couldn't do on the drums.

Wilson is no different. He frequents the drummers' classic left hand cross grip, ergonomics that perhaps delivers less rock power but instead grants the drummer a great range of expression at high velocity with a minimum expenditure of energy, particularly on the snare and the high-hat. With Wilson the listener also gets to hear an exceptionally powerful right foot that delivers rhythms independent of those generated by the other limbs. The result is an intriguing polyphony that belies what the eyes see when watching Wilson. He has an economy of motion at the kit which provokes the illusion he really is not that busy. For example, he will sometimes stop-motion his right hand at the top of the arc before making a decisive strike while the other three limbs in his kit's cast of characters are moving swiftly.

If the listener closes the eyes the realization kicks in that he possesses the same qualities of high-end expressiveness, aesthetics, vocabulary, and velocity as some of the drummers (like Paul Lovens, Han Bennink, and Hamid Drake) we have been privileged to hear in Vancouver. Trio M was worth hearing if just for this one discovery, which of course makes me want to hear Wilson (who by the way composed several of Trio M's pieces) in other contexts.

Back to the gig itself. With a reprise of the melody at the end of the express section, Melford dropped out and Wilson used a rapid deceleration of tempo on the high hat, a moment of silence intervened, and Mark Dresser soloed pizzicato at slow tempo, ending with his trademark right-hand slash against the strings: he hits with such speed that at the hand dramatically continues though the arc and ends up hanging at the horizontal for a moment.

Dresser is one of the sophisticates of the double bass, a true innovator in the way he has exploited the possibilities of combining the traditional acoustic properties of the instrument with contemporary electronic methods. He has discovered methods to enhance the natural vibrations of the strings that are too small to be heard without amplification. His bass has coiled pickups embedded in two strategic places on the fingerboard, allowing him to express as many as three simultaneous pitches on one string and at the same time control the volume of each pitch. The three pitches come from the two lengths above and below where his fingers press the string into the fretboard, and the third is the vibration of the whole string through the instrument.

These techniques are both powerful and beautiful magnifiers that increased the depth and intensity of the music. Midway through the first number of the concert, Dresser created creating a bowed cycle in the deep range of the bass occasionally punctuating it with a plucked the E-string that gradually transited into the cello range. Tucked into all that sound were eerie musics that sounded created totally by a synthesizer, but in fact were the amplified natural harmonics of short lengths of the strings which normally could not be heard by the human ear. What made the effects even more delicious were the happy concurrence of Melford lifting her hands off the keys and manipulating the strings inside the piano, with Wilson softly on brushes.

This song lasted some 33-some minutes. In fact it was not one composition but three, an interpolation of AL (Matt Wilson), The Promised Land (Melford), and Naïve Art (Matt Wilson). The segues, improvisations, counterpoints, instantaneous accelerations/decelerations, and tension-release cycles made the music simultaneously sound like both a total improvisation and a through-composed piece. This was one of the great things about listening to Trio M, they took the audience on a journey through space and time and one was never sure what would happen next. That essence of jazz is exactly what happened during the rest of the concert.

Reference CD: Big Picture By Trio M, www.cryptogramophone.com