There are plenty of recordings of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 Op. 60 (Leningrad), but one rarely gets a chance to hear it in concert. The same could be said, only more so, for Benjamin Britten’s Violin Concerto Op. 15. To have them both offered on the same program is a special treat; thus, Jaap van Zweden and the Dallas Symphony (DSO) had me excited even before they played the first note of this concert at Morton Myerson Symphony Center in Dallas, Texas. As it happens, these two works were composed within a few years of each other: the Britten in 1939 and the Shostakovich in 1941. Although the two composers didn’t meet until 1960, they were mutual admirers and each dedicated major works to the other.

The Britten Violin Concerto was first on the program and it brought back to Dallas the extraordinary Dutch violinist, Simone Lamsma, whose performance of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto last season had made such a strong impression.

Consummate Performance of Neglected Masterpiece!

Lamsa’s rendering of the Britten concerto was beyond impressive. Her technical and intellectual control of the piece convinced me that Opus. 15 is a neglected masterpiece. She soared into the top register of her instrument with total assurance and tossed off the difficult left-hand pizzicati with perfect panache. Such rock-solid playing enabled one to savor the musical argument, and it was profoundly satisfying.

The final movement of this volin concerto is a Passacaglia – a set of variations on a bass line - and surely one of the most imaginative examples of the form by this composer or any other. It starts with a doleful theme in the trombones - performed with perfect intonation by the DSO brass - and goes on from there. It was mesmerizing to hear Ms. Lamsma ring changes on the theme while behind her various sections of the orchestra were going through a series of inventive and complementary permutations on their own. The movement ends quietly and sadly, not unlike the ending of the Berg Violin Concerto.

Lamsma played magnificently, with van Zweden and the DSO providing impeccable accompaniment.

Instrumental Britten Revived and Re-instated

Over the course of his lifetime, Britten was frequently criticized for being, in effect, "too clever." Critics claimed that his music was superficial, that it had no depth.

With the passing of time, however, many have come to appreciate the extent of Benjamin Britten’s originality. For some, myself included, he is the greatest composer of opera and song that England has ever produced, and I believe his instrumental music will continue to grow in stature.

The Violin Concerto Opus 15 is often written off as “an early work,” but as is the case with Mozart and Mendelssohn, many of Britten’s early works are among his finest. Let me give you just one example of what might be mistaken simply for ‘cleverness’ in this concerto. It’s an extraordinary passage in the Scherzo movement for piccolos and tuba. A ‘clever’ and unusual combination? Perhaps! But exciting as well, when one realizes that, in combination, Britten has given these often stereotyped instruments striking new dimensions of expression.

I have always considered Benjamin Britten to be one of the great masters, but before this concert I had never fully appreciated his Violin Concerto. I am deeply grateful that Lamsma and van Zweden provided the key to such a work. Incidentally, the Violin Concerto has a Canadian connection; Britten completed its composition in St. Jovite, Québec.

Making a Case for “Leningrad”

After intermission came the much longer Symphony No. 7 (Leningrad) by Shostakovich, perhaps best known for its Bolero-like first movement (Allegretto) which builds from a soft, repeated snare drum figure to a monumental climax.

Unfortunately, Shostakovich’s theme for this episode is every bit as trite as Ravel’s Bolero and, like its counterpart, it does not improve with repetition. No wonder Bartok made fun of the Shostakovich tune in his Concerto for Orchestra!

That said, Maestro van Zweden made the best possible case for the 7th’s opening theme. He started the section with a virtually inaudible snare drum establishing the rhythm – marked ppp in the score – and built the volume with meticulous care. When the climax came, it was certainly impressive – and earsplitting – as the extra brass (called for in the score) were added to the already large and powerful orchestra. As usual, the magnificent McDermott Concert Hall of the Morton Myerson Symphony Center handled the huge volume of sound with ease.

For me, however, the best parts of the Leningrad are not the towering climaxes in the first and last movements but the second movement (Moderato) and the third movement (Adagio).

The second movement (Moderato) is hauntingly beautiful, beginning with the loveliest oboe solo Shostakovich ever wrote, beautifully played by Erin Hannigan. Then come several sections recalling Mahler, especially in his use of woodwinds in various combinations. Then an entirely original touch - at least in my experience - as the bass clarinet (Christopher Runk) plays an eloquent, extended solo accompanied by the harp, two flutes in their lowest register and an alto flute. This combination makes for an uncommon, uncanny sound. Once again, van Zweden and the DSO played to perfection: tempo just right; rhythms crisp; tonal quality exquisite.

The Adagio movement opens with extremely disturbing block chords that move into music expressing all kinds of lamentation. This is followed by the moderato risoluto section, a kind of 'danse macabre.' Van Zweden brought out the syncopation driving the music forward and made sure we also heard the rich sonorities of the Dallas strings, especially the double basses.

First Violins of DSO Savor Challenge!

This is music of endless soul-searching, probing the best and the worst of the Russian spirit during one of the worst periods in the country’s long and troubled history - the siege of Leningrad by the Nazi forces in an unimaginable campaign lasting two and a half years.

If music can adequately express such horrors, the Shostakovich Seventh Symphony is where you will find it. It is not easy listening, but like all great art, it penetrates and articulates the human condition in a universal language.

In closing, I must applaud the members of the first violin section of the Dallas Symphony led by Emanuel Borok and Gary Levinson. In this symphony, there is one passage after another where they must perform death-defying high wire acts in their instrument’s highest register. This is cruelly exposed music. Not only did they play these passages with unfailing accuracy; they also gave them superlative shape and character. This was first-class playing by any standard and Dallas is fortunate to have such gifted and dedicated musicians.

Paul E. Robinson is the author of Herbert von Karajan: the Maestro as Superstar, and Sir Georg Solti: His Life and Music, both available at Amazon.com.

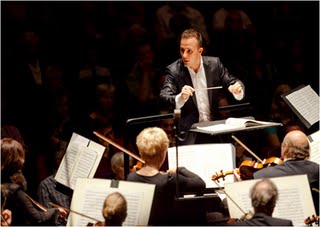

Photo by Marita: Maestro van Zweden and DSO in rehearsal

Labels: Benjamin Britten, classical music blog, Dallas Symphony, Dmitri Shostakovich, Jaap van Zweden, Simone Lamsma